There is a lot of talk about negativity in elections, and as measured by Wesleyan Media Project (and Wisconsin Advertising Project) coding, there is much more of it on the airwaves than there was a decade ago. Yanna Krupnikov (Stony Brook University) writes for us on the effects of negativity and why timing is everything.

On September 30, 2014, Rob Astorino, a Republican candidate running for Governor of New York, aired an ad designed to warn voters about his opponent’s questionable ethics. Astorino’s ad was a “remake” of Lyndon B. Johnson’s 1964 “Daisy Girl Ad,” and used identical imagery to tell people that his opponent, incumbent Andrew Cuomo, may end up in jail.

Although Astorino’s ad is unusual by virtue of being a “remake” of a “classic” ad, it is just one of the thousands of negative ads that hit the airwaves every national election. Indeed, as the Wesleyan Media Project reported on October 14, half of the campaign ads in 2014 gubernatorial races have been negative. Astorino, it seems, is not alone.

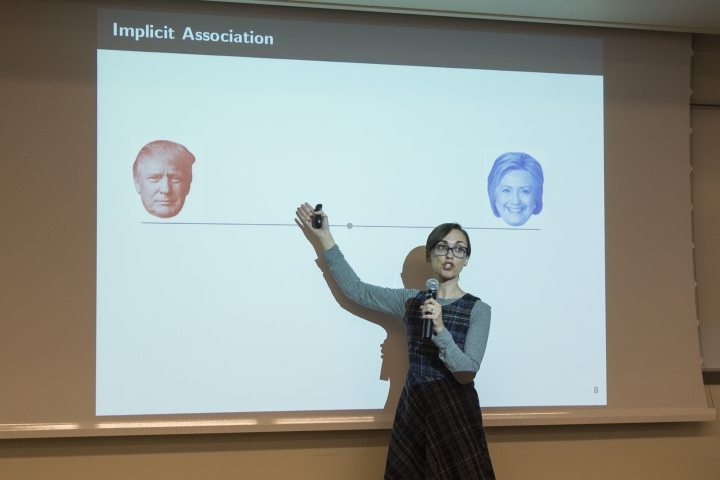

Voters will often report that they dislike ads like Astorino’s — negative ads designed solely to criticize an opponent. But dislike aside, do these ads affect the way people navigate politics? My research has focused on this very question. In my work, I show that negative campaign ads can and often do affect people, although this effect is not always detrimental. Rather, the effect of negative advertising depends on its timing.

In my research I rely on surveys, real advertising data and large national experiments. I use these types of data to show that early on in the campaign negative advertising actually helps people make candidate choices. Negativity, data suggests, is quite powerful!

It is more memorable, and often contains more real issue information than positivity. In fact, my research shows that people who live in media markets that receive more positive ads than negative ads early on in a campaign have a more difficult time making candidate choices, and are somewhat less confident in the choices the do make.

The effect of negativity, however, changes as a campaign nears Election Day. Late in the campaign negativity can have a more detrimental effect on people. When people see negative ads after they have made their candidate choices, negativity can make them more doubtful and less confident about the choice they have made. Ultimately, then, my research shows that this doubt can make people less likely to turn out and vote.

We can think about the effect in this way. Suppose in October a person picks the Republican candidate over the Democratic candidate. Let’s say that after making this choice, the voter is then bombarded with negative ads criticizing the Republican. The voter is then left with a set of unsatisfying options. She already knows she does not like the Democrat, so switching party lines is not a reasonable option. She could vote for her initial preference, the Republican, except now she is no longer confident in her choice due to the negativity. Her final option, then, is to stay home, and my data suggest that negativity leads many people to take this third option. In fact, tracking the effect of negativity from 1980 to 2000, I show that negativity aired late in the campaign consistently leads people away from voting.

When it comes to voter turnout, then, negativity is a double-edged sword. When aired early in the campaign it can help people make important political choices, but aired late in the campaign it can lead people to doubt the very choices they’ve made, leading them away from the polls.

While much of political science research has focused on the way negativity affects turnout, these types of ads have even broader implications. First, the effect of negativity depends on the candidate who sponsors the negative ad. In a forthcoming article with Spencer Piston, we show that people respond quite differently to negative ads sponsored by Black candidates than they do to negative ads sponsored by White candidates. Similarly, Nichole Bauer and I show that people also have different responses to campaign ads aired by female candidates than to negative ads aired by male candidates.

Second, it is possible that even for people who do turn out to vote in spite of negative ads, the negativity of a campaign still leaves an imprint on their political perspectives. As Samara Klar and I demonstrate across a series of studies , when people are reminded of partisan disagreement (the very disagreement that negative ads make crystal clear) they turn away from partisanship. Faced with partisan negativity people hide their party, avoid partisan discussion and they avoid engaging in any type of political activity that may betray them as partisans.

While the short-term costs of negativity may be turnout, the long-term costs of negativity may lead to more profound consequences for political parties: a decline in the types of supporters who are willing to proudly proclaim that they are partisans.