This post from Travis N. Ridout was first published at The Blue Review, a journal of popular scholarship in the public interest at Boise State University. Click here for the original post.

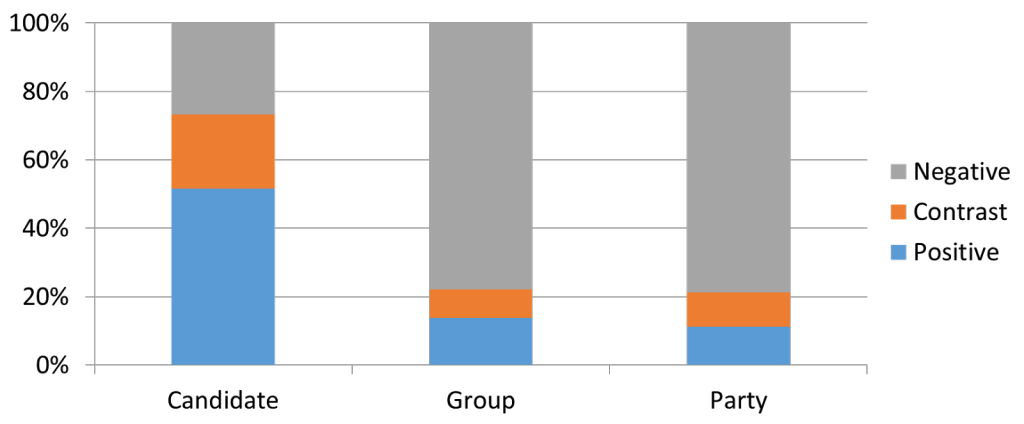

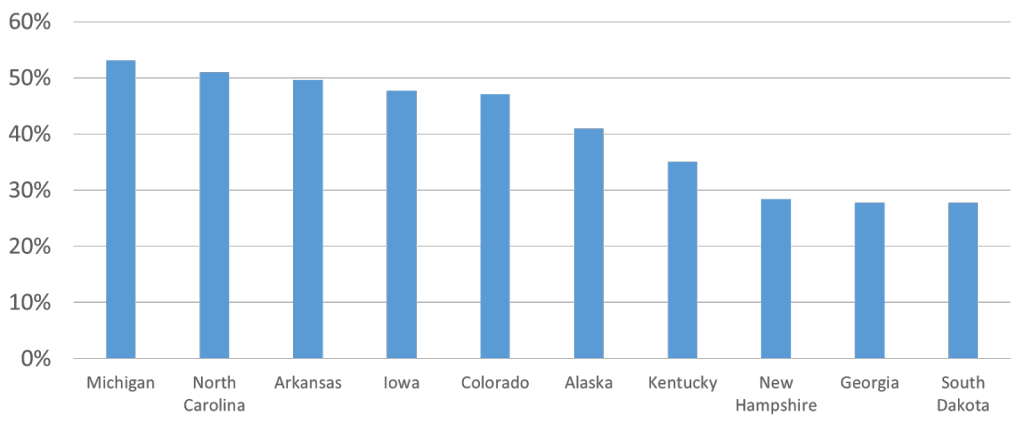

It used to be that candidates paid for most of the political ads that aired on their behalf. If they were involved in a highly competitive race, their political party might have jumped into the “air war” to pay for some ads backing the candidate. Occasionally, an interest group even waded into the political ads game. But in the past decade, that traditional balance of advertising sponsorship — with candidates the largest players, followed by parties — has been upended. Groups are now the second largest advertisers, and in some races they are now number one. For instance, in the 2014 Senate races in North Carolina and Michigan, over half the ads that aired were paid for by groups. Overall, groups sponsored just under 30 percent of the ads that aired in elections last year for House, Senate and governor races.

One reason that groups have become so much more prominent in campaigns is that recent Supreme Court decisions, including FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life in 2007 and Citizens United v. FEC in 2010, have struck down government campaign finance regulations, making it easier for money to get into the system. At the same time, the type of group involved in campaigns has shifted. In the past, membership-based groups such as the National Rifle Association, Planned Parenthood and labor unions were some of the biggest group advertisers. Today, the biggest group advertisers are organized as 527s, 501(c)s (including “social welfare” groups), and Super PACs. Groups using these organizational forms may raise and spend unlimited dollars on advertising, have almost no restrictions on what they may say in the advertising, and in the case of 501(c)s, there is no requirement that the group disclose its donors.

According to data from the Wesleyan Media Project, which I co-direct with Erika Franklin Fowler and Michael M. Franz, the biggest group spenders in 2014 House, Senate and gubernatorial races were the Republican Governor’s Association ($22 million), Senate Majority PAC ($22 million), Crossroads Grassroots Policy Strategies ($21 million), Americans for Prosperity ($17 million) and House Majority PAC ($15 million). With the exception of the RGA, the names of these groups reveal nothing as to whether they are on the left or the right or whether they are affiliated with Democrats or Republicans. And most Americans know next to nothing about these groups other than their names convey the idea they are people-powered, grassroots organizations. Who could object to Americans who are in favor of prosperity, after all?

Figure 1: Political ads by tone and sponsor, 2014

Research in political science finds that ads aired by generic groups about whom people know little are much more effective than ads aired by candidates or groups about which people know a lot — and Americans know very little about these groups with their patriotic-sounding names. In short, ads from unknown groups are perceived as more credible. Think of it this way: if you see an ad that is approved by a candidate, you take the message with a grain of salt. After all, the candidate is probably distorting the truth, just saying anything to get elected, right? But if you see an identical ad and the sponsor is, let’s say, Patriots for American Liberty and Opportunity, then you might assume that the group is backed by thousands of everyday Americans who have donated a few dollars to this organization with which they agree. In truth, this made-up group is probably little more than a post office box in Arlington, Virginia, and a few billionaire donors who are either seeking influence or have an axe to grind.

So we’re left with a situation in which the most effective ads are run by organizations that are little more than legal entities that can collect and spend unlimited dollars and may not even disclose their donors. This can’t be a good situation, but what can be done about it?

Some reformers would love more regulation on raising and spending campaign money, but the U.S. Supreme Court has made clear that it deems more campaign finance regulation as unconstitutional. Yet there is one reform that was most recently upheld as constitutional in Citizens United v. FEC and could potentially limit the influence of group-sponsored advertising: disclosure of the group’s largest donors. It is also possible that the effectiveness of that disclosure might depend on 1) who is backing the group — whether a few rich donors or many small-dollar donors — and 2) the form of the disclosure — whether in the ad itself or from the news media.

Figure 2: Top states for U.S. Senate ads sponsored by groups, 2014

In order to investigate this possibility, we conducted an online experiment using a sample of 1,200 Americans. All participants read a news article about a fictitious state senate race and then answered questions about their impressions of the candidates described in the article. We then divided participants into one of six groups:

- The first group watched an attack ad that contained a disclaimer that the candidate sponsored the ad.

- The second group watched the same ad but attributed sponsorship to a fake group, the Center for American Democracy.

- In the third condition, participants read an article describing the group as supported by many small donors before watching the group’s ad.

- The same occurred in the fourth condition, except the article described the group as backed by a few rich donors.

- In the fifth condition, participants watched the group-sponsored ad with an additional disclaimer that the group was backed by many small donors.

- In the final condition, participants watched the same group-sponsored ad, but the disclaimer listed the top four donors to the group and the amount that each gave.

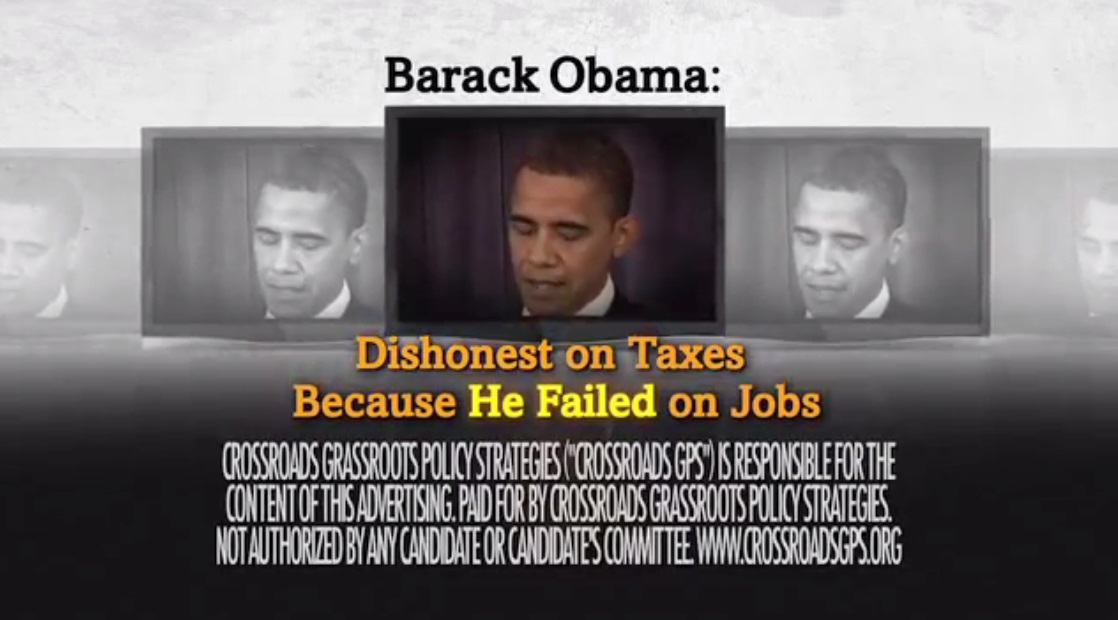

Screen shot of one of the fake ads used in the Wesleyan Media Project study.

After watching the ad, all participants in the experiment rated the credibility of the ad, its trustworthiness and expressed a choice for the attacked or the attacking candidate. Just as predicted by previous research, the group-sponsored ad with no disclosure was rated the most credible, closely followed by the group-sponsored ad combined with the news story describing the group as backed by small donors. Disclosure within the ad — whether large-donor or small-donor — reduced its credibility to be on par with that of the candidate-sponsored ad.

The least credible ad was the group-sponsored ad combined with the news story revealing that the group was backed by a few large donors. The pattern was similar for the ad’s perceived trustworthiness, except this time the group ad combined with the “small donor” news story was rated the most highly. In short, disclosure of donors tended to reduce the ad’s credibility and trustworthiness, putting it on par with the candidate-sponsored ad. The one exception was the group ad paired with the news story describing the sponsor as a grassroots, small-dollar organization; this ad was rated quite highly.

When we look at vote choice, the interest-group ad with no disclosure is the most effective at moving voters away from the attacked candidate, but the ad become less effective under conditions of disclosure, regardless of whether it is from the news media or in the ad itself and regardless of whether the group is large-donor or small-donor.

This experiment shows that disclosure — whether mandated by the Federal Election Commission or Congress or taken on by the news media — can help to level the playing field for candidates. When there is more information about who is backing the group, the ad’s effectiveness is lowered, resulting in an ad that about equal to a candidate-sponsored ad in terms of its persuasive power. And thus the incentives for donors to give their money to groups as opposed to candidates is lessened somewhat.

##

Read the full paper: Sponsorship, Disclosure and Donors: Limiting the Impact of Outside Group Ads.

Travis Ridout (Ph.D., University of Wisconsin – Madison) is the Thomas S. Foley Distinguished Professor of Government and Public Policy and associate professor in the school of Politics, Philosophy and Public Affairs at Washington State University where he teaches courses in American politics, elections, media and politics, research methods and statistics. He is also co-director of the Wesleyan Media Project, which has tracked all political ads aired in the United States since 2010.